In political conversations about Puerto Rico, there is a phrase that comes up again and again. Whenever Puerto Ricans question U.S. policy, federal control, or the island’s political status, someone inevitably responds with a dismissive remark: “If you don’t like it, then just renounce your U.S. citizenship.”

For a long time, I didn’t give that statement much thought. It’s usually not said as a serious proposal, but as a way to shut down discussion. Still, it lingered in the background as one of those rhetorical weapons that gets used when the conversation becomes uncomfortable.

Recently, however, I heard a content creator mention that there was, in fact, a Puerto Rican who actually took that path—someone who formally renounced U.S. citizenship. That moment made me pause. If someone really did this, what happened afterward? What were the consequences? And what does that case actually reveal about Puerto Rico’s political reality?

That question led me to a well-documented historical case: Juan Mari Brás.

Juan Mari Brás was a Puerto Rican lawyer and a prominent figure in the independence movement. In 1994, while outside the United States, he formally renounced his U.S. citizenship using the legal process recognized by the U.S. government. The renunciation was accepted, and documentation was issued confirming the loss of nationality.

So yes, the act itself did occur. But that is usually where the story ends in casual conversation—and where important context gets left out.

Puerto Rico is not a sovereign country under international law. It is a U.S. territory. That distinction is not semantic; it is foundational. Territories do not control nationality in the same way sovereign states do. They cannot issue an internationally recognized nationality that functions independently of the governing power.

When someone renounces U.S. citizenship without holding another nationality from a sovereign country, they risk becoming stateless. Statelessness is not an abstract concept or a political slogan. It is a real legal condition with tangible consequences.

In the case of Juan Mari Brás, those consequences were not theoretical. Renouncing U.S. citizenship created complications related to travel, documentation, and legal status. International movement depends on recognized nationality and valid travel documents. Civil and political participation can also become complicated when citizenship is no longer clearly defined. Even residency raises questions under a territorial system where nationality and governance are externally controlled.

There is a particular irony here that is difficult to ignore. In a non-sovereign system, rejecting the nationality imposed by that system can place a person in legal limbo—even in their own homeland.

Years later, Juan Mari Brás received a Puerto Rican citizenship certificate issued at the local level. That document carried symbolic and administrative meaning within Puerto Rico, representing identity and political expression. However, it did not function as an internationally recognized nationality. It did not replace U.S. citizenship within the global legal framework, nor did it grant the rights associated with sovereign citizenship.

This case is often referenced as proof that Puerto Ricans can simply renounce U.S. citizenship and exist as Puerto Rican nationals alone. But when examined in context, it demonstrates something very different. It exposes the limits of Puerto Rico’s political status and the constraints imposed by a territorial framework where identity and sovereignty are not aligned.

There are important takeaways here. On one hand, the case forced a public conversation about Puerto Rican identity and nationality. It challenged assumptions and highlighted contradictions in the existing system. For many, it became a symbol of political resistance and personal conviction.

On the other hand, it also revealed serious risks. Statelessness carries instability. This path is not practical or safe for most people with families, careers, medical needs, or obligations that require legal clarity. Most importantly, the act itself did not resolve Puerto Rico’s political status. It highlighted the problem, but it did not change the framework.

When people casually tell Puerto Ricans, “If you don’t like it, just renounce your citizenship,” they are oversimplifying a deeply complex reality. That statement ignores history, law, and consequence. It turns a serious structural issue into a slogan.

I’m not a historian, and I don’t claim academic authority. Like many Puerto Ricans, I’m learning as I go—reviewing historical records, legal documents, and publicly available information, and sharing context that has often been missing from these conversations. Whether that omission was deliberate or accidental, the result is the same: important parts of our story are rarely discussed.

These conversations deserve more than talking points. They deserve context, documentation, and honesty. Understanding what happened in cases like Juan Mari Brás’s helps us ask better questions about where Puerto Rico stands today—and where it might go next.

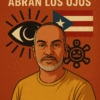

I am Edwin Ortiz, and this is the Puerto Rico and Spain Initiative